Writers’ festivals are ephemeral by nature and difficult to capture the essence of, but this year we were lucky to have CuriousWorks film the day for us. The video they’ve cut together does manage to convey something of the congenial atmosphere. Given the focus on writing and writers, however, we thought we’d ask for some words from some of the writers who attended, participated and volunteered. For a number of people, it was their first time attending a writers’ festival.

“The first things I saw were the knitted-home made blankets draped over plastic chairs in the Gumbramorra Hall. I thought, oh, that’s so lovely! I then glanced at the stage, and there was a large shabby chic baroque throne that looked like it could fit three writers. A batch of pink balloons hovered nearby. Oh, I mused, that looks different! I didn’t know it yet but the blankets and the throne set a tone which was to hum throughout the day — relaxed, unaffected, friendly, wise.

We apparently shouldn’t judge books by covers but I did a little that day, prompted by all the cosy signs, which made the Addi Road Writers’ Festival instantly feel familiar even though I’d never been to one: the bedraggled 80s writers couch in the Greek theatre, a toddler napping in its mother arms, more balloons. There were sounds too that were homey, briefly interrupting but what happens in life: planes overhead, a dog whimpering during a talk, the murmur of people chatting and laughing outside the theatre. There was no mention of hashtags or @’s. Yay! I helped on the front door for awhile, watching an interesting-looking public stream in, draped in lace, hats, unusual ear rings, cycling gear and t-shirts with fun commentary. I learned there is a Sydney salon that only cuts curly hair.

I suppose this all meant I really felt the words on stage. They spoke of shame hangovers from writing memoirs. They spoke of corporations pressuring newspaper editors not to run stories. They spoke of feeling nervous about speaking. Thankfully the blankies were there.”

Jackie Dent

“Readers, writers, comics, booklovers, and community organisers gathered to listen to an opening address that started with Uncle Wes Marne to ‘have a good day’. A simple sentiment that set the tone for a day of conversation, inquiry and the buzzing of creative minds and thinkers. Authors, poets and comics spoke casually and authentically, and moderators joked about needing a drink as they were nervous. This was a showcase of art as much as it was a thought-provoking series of discussions, pointing us to our own entryways into thinking anew about various topics. It is festivals such as these, made through grassroots community organising, where one felt the Addi Road community come alive and accessible to creatives at all levels of their career, as well as lovers of the craft.

I felt a truly collective presence throughout the day. Not only with each panel or artist spotlight, but even seeing the crowds buzzing around between the two spaces, friends and creatives reuniting or meeting for the first time. I discovered new poets and moderators. Writers’ festivals have in the past felt like an exclusive space to me, spaces that I, even as an audience, am too far away to enter. The success of ‘New Lines’ was not only its stellar lineup, but also in its ability to rid itself of elitist and exclusionary boundaries. The intention of each panel was felt with a natural and free-flowing sense of unity that allowed each panelist to speak frankly and for themselves. The festival left me grateful, and warm-hearted at knowing that collaboration and community truly do go hand in hand. Once we see them in action together, what have we but the simple pleasures of spending the day speaking, listening, understanding, and thinking, much long after the day is over?”

Huyen Hac Helen Tran

“Prior to the Addison Road event, I’d never been to a literary festival—nor had I felt any desire to. In Melbourne, the city in which I live and work, these festivals seem rather heavy on the culture industry and a little light on culture. But what do I mean by ‘culture’? As Raymond Williams once put it, ‘culture is ordinary’, which was his way of saying that all culture is grassroots culture, or that it at least starts off that way before being strategically hot-housed in institutions.

The whole day of the Addi Road Writers’ Festival was memorably free of the stifling air of coteries, or of the ceremonious prostration before Books and Ideas that passes itself off as cultural engagement. The stage in the Greek Theatre was representative of the atmosphere: moderators were seated on an armchair while panellists sank into an adjoining couch on what looked like the set of a kitchen-sink realist play. Suffused by a warmth of the familiar, it proved a congenial environment in which to talk about the reparative powers of poetry, of faith in the durability of the written word (heightened by the precarity of life under present conditions), with Robert Adamson (sadly, Prithvi Varatharajan had fallen victim to the pandemical virus and was prevented from joining us).

So many of Robert’s poems are about reparative habits of accommodation that allow us to adapt to everything from year-round seasonal changes to the singular deaths of our intimates. Poetry, so frequently and speciously thought of as belonging to its own rarefied province of finicky verbalists and feral jongleurs, is a plea for the restitutive powers of the ordinary. ‘The poem,’ as Wallace Stevens once wrote, ‘is the cry of its occasion. / Part of the res itself and not about it.'”

James Jiang

“As a child, I was discouraged from reading comics/graphic novels since they were regarded as frivolous and shallow by the adults I was surrounded by. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

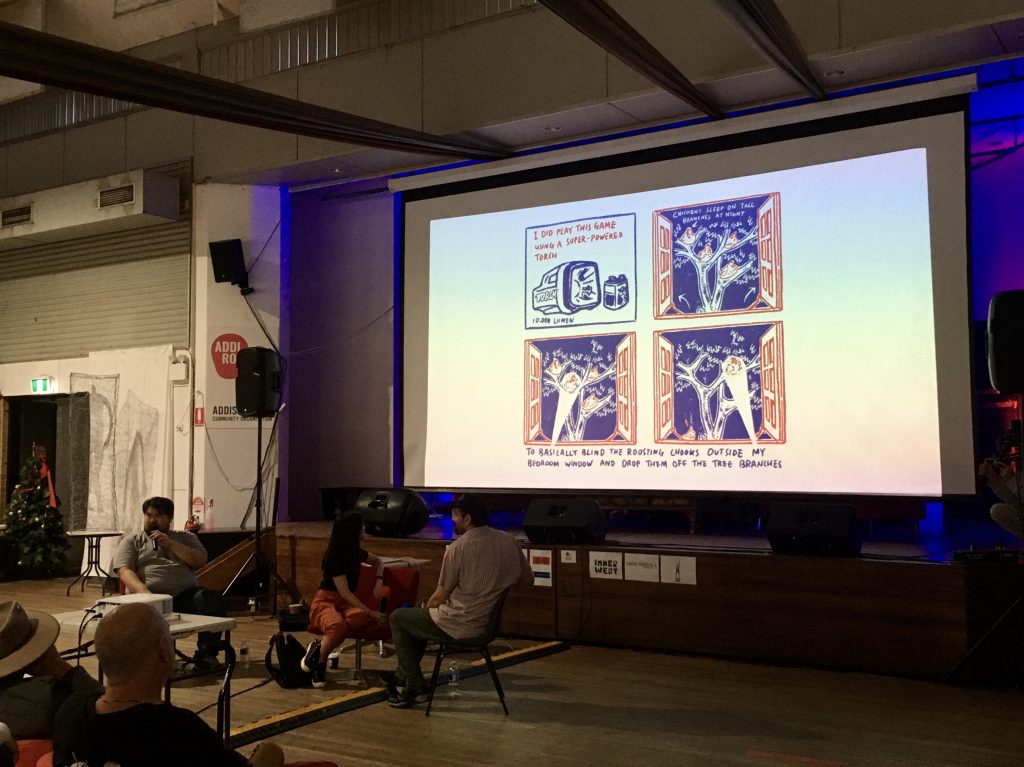

The panel discussion between Safdar, Meg, and Jin was the highlight of the festival for me. As I watched the panelists present their work, I came to realise that autobiographical comics are much more than just pencil drawings and speech bubbles. This session introduced me to a powerful medium where trauma, identity, and memory are explored through multilayered narrative structures – which also made me wish I had at least some artistic talent!

Safdar Ahmed presented one of his early works, The Good Son, which explores his Indian-Australian upbringing and troubled relationship with his father as an adolescent. It was fascinating to see how Safdar was able to explore the multiple versions of ‘self-identity’ through his work. Meg O’Shea presented her work investigating the complexities of her identity as a Korean-Australian adoptee. I found Meg’s work, which chronicles her search for her Korean birth mother, to be captivating. Jin Hien Lau did a great job moderating the conversation and talking about incorporating themes of race and politics in his work.”

Deniz Agraz

“The festival was a refreshing reminder of what it feels like to attend a festival in-person and experience the simple pleasure of partaking in a lively panel discussion or listening to the passionate recitation of an author with a live audience.

There was never a dull moment as I jumped from one exciting conversation to the next between the concurrent talks taking place at the Gumbramorra Hall and the Greek Theatre. I felt spoiled being immersed in a wide range of topics including the power of poetry, the ethics of memoir, defining good journalism and the thrilling intersection of western rock and Vietnamese folk music.

I particularly enjoyed listening to the heartfelt poetry of Ethan Bell, an Aboriginal artist based in my local suburb of Campbelltown, and the delightful comic panel “Drawing Your Own Bed and Lying In It” featuring Safdar Ahmed, Meg O’Shea and Jin Hien Lau.

The festival’s range of transnational artists hailing from Ireland, Indonesia and across the world exploring issues through an interdisciplinary lens provoked new lines of thought and inquiry for me.

To top off all the wonderful memories I took away from the festival, my new favourite graphic novelist won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award a few days later and I had managed to secure a selfie and a signed copy of his book as the ultimate memento.”

Kobra Sayyadi