I meet Fury and Sorrow in the Inner West of Sydney. They have fled Afghanistan by different paths and means. Fury has been here six days; Sorrow six weeks. Old friends come together again.

I talk to Sorrow for a long time in a street-food café inside the grounds of the Addison Road Community Centre. Aged 21, she engineered not only her own escape from Kabul, but that of her mother, her sister and brother, and 15 other young women she studied with at university. The Taliban don’t just hate women, Sorrow tells me, they hate the educated, they hate anyone that can speak English, they hate artists, scientists, writers… “Anybody like this, they will die them”. Then Sorrow corrects herself and says, “kill them”.

She describes “the peace, the safe feeling I have, especially here in this place where we are.” But Sorrow is well aware of her own mixed feelings. She has what might be called survivor’s guilt after arriving here in Australia to start a new life. There are still two other sisters with families, her friends, all these “girls and boys” trapped in Afghanistan. Sorrow does not sleep well and her thoughts travel all the time to those she left behind.

“I know good men. I love the ones who treat me equal and free.”

The former business student ran her own emporium in Kabul, advancing her aspirations to become a leading Afghan designer as well as bringing together handicrafts from fourteen different ethnic groups across the country. Sorrow loves textures, clothes, colours, “dark colours especially”. Looks are important to her. She straightens her crimson coat, pats her blue jeans, checks her nails, pulls her hijab over her long dark hair. An elegant metropolitan modern woman. She studies another young woman arriving at the café, absorbing her aesthetic and energy, observing alternative cultural forms of attractiveness and pride.

After growing up in Kabul’s progressive atmosphere, Sorrow and her female friends found themselves in hiding, too afraid to leave her family apartment for so much as a bottle of water. She recalls the Taliban arriving in the city. Being frightened for what they might do to her… the random street interrogations for any woman walking alone, the threats of rape or forced marriage. “They are like dogs,” she says bitterly.

Have the Taliban made her lose faith in all men, I have to ask? “No,” Sorrow says. “I have a father, a brother, I know good men. I love the ones who treat me equal and free. Who see me equal and free. I love them.”

Fury sits apart from the conversation, speaking to other people seated at the café. Her eyes cut across the wide spaces to stare directly at and right into you. Her brown hair is in a ponytail, clear complexion, country girl beautiful. Also aged 21, Fury made her way here alone, a former women’s rights leader who had no choice but to run, and to run early. Her power as an individual – and her isolation – radiate like a force field. She and Sorrow were friends in Kabul; indeed Sorrow sheltered her as civil society begun to unravel in the city. Until Fury fled, one week sooner than Sorrow, sensing the looming danger of the Taliban, especially for the likes of her, but taking much longer to make her way to Australia. In Sydney, against all the odds, Fury and Sorrow are reunited.

It turns out Fury and Sorrow need to Sydenham Station to catch a train further west to where they are living together in temporary accommodation with the other 15 Afghan girls who have also escaped. Sorrow leaves Fury and I for a moment. She need to get her bags from inside the offices of the Addison Road Community Organisation in Marrickville where they are learning English and getting help with permanent visas. This place has become a home away from home for them as they try to figure out their next steps and meet people who can assist them with food, clothes, work, accommodation.

To sit alone in my car with Fury is almost too much to deal with. She treats our conversation like a life-or-death moment, launching into a speech that might just as well be an urgent address to the United Nations: “I am not grateful to be here. I do not want to say thank you. I do not want to be a refugee. Do not use this word ‘refugee’ on me. I see what is here. I have these things in my own country. I want to be in my own country. I want my home.”

“The Taliban take my motherland. But they cannot take my mind.”

“Why is this happening to me, to all these people from Afghanistan? It is just a game. I cross the border into Pakistan and I must have a passport and be covered in black, head to toe,” she says with disgust. “But the Taliban can come and go with guns and with artillery. It is a game,” she says again. “So they take my motherland. But they cannot take my mind. I wish to be the first woman president of Afghanistan. This is what I will do. They cannot stop me.”

In Afghanistan, Fury liked to wear a chador, covering her hair. It was an act of cultural and religious pride. Her choice. Not some infringement on her identity or gender. She was a progressive young Afghan woman lobbying for even more advances. You have to understand most of these young people have grown up like that. Almost 65% of the population is below the age of 25, a half of them below the age of 15, one of the youngest nations in the world.

They have never had to live with Islamic extremism or its tenets as a way of life. The change that has come is brutal and sudden. Now Fury dispenses with her chador altogether, dresses in an uncovered and more casual way, touches her new clothes like she is still coming to terms with recognising herself in this new place. When the time is right she wants the Taliban to see her.

Fury is a writer too. She wants me to know she was like me; and that she is like me. She says she had to leave her laptop behind, and with it her novel manuscripts, as well as all her family, everything she owned, carrying only five of her beloved books “in secret” across the border. A young woman with her own phone and a few books is a dangerous thing to be. Fury wants me to listen carefully; Fury wants to speak to President Biden about “the game” in Afghanistan. Fury wants to fight for her country. “I am not a refugee.” Her anger expended, there is a moment near tears, the bare fact of trauma revealing itself before being controlled and suppressed.

Sorrow returns with her bags. She jokes, a little apologetically, “We have to carry so much now. All our things.” One bag with the necessary papers, a whole world of who they are and might be. What you carry is what you are.

“I like the colour of the tree that is all purple. All its purple flowers falling on the ground.”

We drive together to the railway station. Back at the café, Sorrow used her iPhone to play me a ‘sura’ from the Koran, a voice reciting, in calling cries that are like a song, the beauties and righteousness of “the Sovereign One”. “I play this,” Sorrow says to me, “when I am unhappy. It makes me feel better. It makes me become still.”

I try to return the favour on our journey to the station by playing them The Rolling Stones’ ‘Waiting on a Friend’, the song straining from the tiny speaker of an iPhone. Sorrow is only half-interested, chatting on her iPhone. Fury listens like every particle of the song is a mystery that needs to be answered. I’m embarrassed by how feeble it sounds.

We stop the car and I ask to take a photo with them. “Sure.” The two young women step out into the overcast morning, the wind fresh with the scent of oncoming rain. They brush their hair back with their hands; look at themselves in their iPhone make-up mirrors. Fury becomes ‘Farhat’; Sorrow becomes ‘Marwa’; two ordinary young women laughing with one another and comparing how they look. They take their own photos after I take mine, then they wave me goodbye, telling me I am now “one of our besties” as they step on down the street to catch the train to where they are living.

At dinner that night, their phones will be brought out to show activist friends in Australia a few pictures of the dead bodies they have seen, torture victims left in the street, the finger webbing spliced up to the bone and beyond by secateurs. Images that have become as familiar to them as make-up selfies and shopping. Images shown almost casually because they are so much a part of what has happened to their world. They recognise the horror in them, but the horror has been degraded, if only to help them live with having seen it on their doorstep.

I think about what Farhat said of her ambition to return to Afghanistan and lead her country. I think she has the strength to do it. I think, too, of what Marwa said to me about the different coloured trees in Australia. “This first tree that I saw, I do not know its name, but all the leaves were red on one side and green on the other. I have not seen anything like it before. I like this very much. And I like the colour of the tree that is all purple. All its purple flowers falling on the ground. It is very beautiful.”

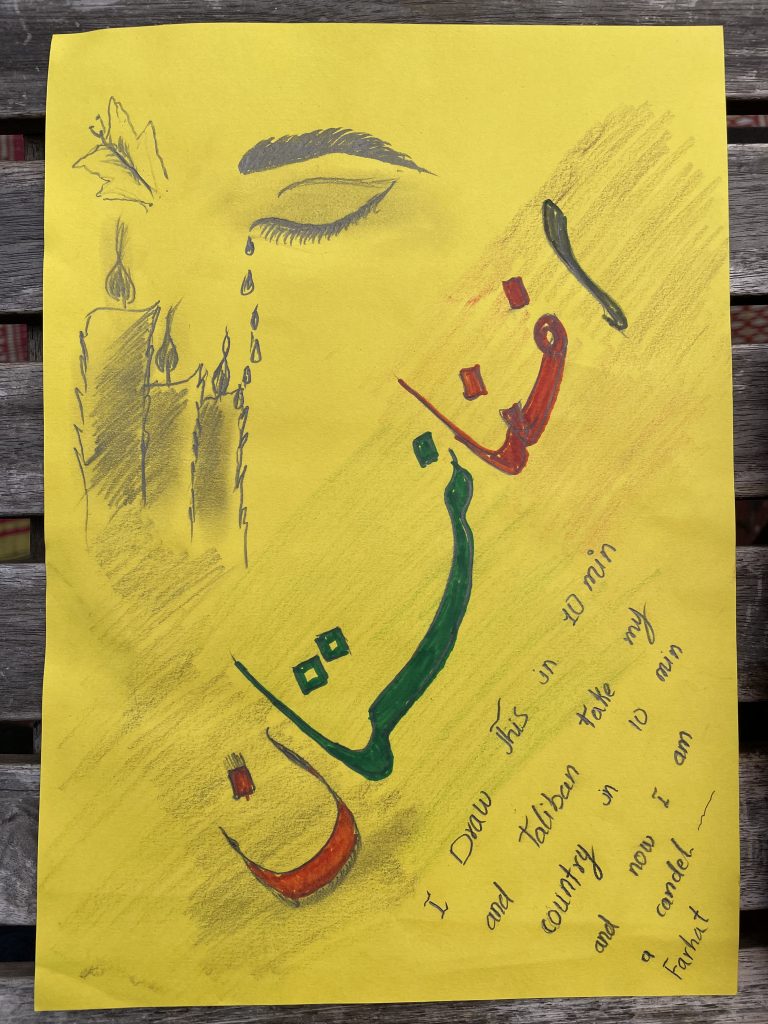

Main photo – Marwa/’Sorrow’ at Addison Road Community Organisation in Marrickville. You can hear more about Marwa and her journey in an interview with Fran Kelly on ABC Sydney 702 here.